![Neil Cashman]()

Neil Cashman

Neil Cashman and Blair Leavitt have been willing to climb out onto separate limbs – perhaps farther than many colleagues would be willing to go – in their respective efforts to find a treatment for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Dr. Cashman is parlaying his expertise in prions – a type of protein that, when misfolded, becomes toxic to brain tissue – to pursue the idea that another type of protein, called, SOD1, behaves much the same way.

Dr. Leavitt, meanwhile, is challenging the notion that motor neurons are the only key to stopping the disease. He has found evidence that muscles themselves – which are easier targets for therapies – can have an “upstream” effect on the motor neurons.

Neither scientist has had an easy time making his case. But they consider the risk worth taking, considering the cruel nature of their target: a disease that causes people to lose control of their muscles, and in most cases, die within three to five years after symptoms first appear.

Dr. Cashman, a Professor of Neurology and Canada Research Chair in Neurodegeneration and Protein Misfolding, says his work (some of it published in March 2014 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences) “represents a paradigm shift, and it’s always difficult to get over that kind of threshold.”

Dr. Leavitt, a Professor in the Department of Medical Genetics, spent three years from the time he first submitted data to convince a journal (Nature Communications) to publish his findings in December 2013.

![Blair Leavitt]()

Blair Leavitt

“Science is self-correcting, but it’s inherently conservative,” he says. “New ideas have to have enough data before they oust the old. So, if something is out of the ordinary, it’s going to have to reach a higher bar. The papers that have been the easiest to publish in my career have been the least interesting… Then, when I have something that’s novel and exciting, it’s torture to get it published. But you have to accept that that’s part of the process.”

A mistake leads to a discovery

Underscoring that very point, Dr. Leavitt’s investigation began with an idea that turned out to be completely wrong.

A postdoctoral fellow, Kevin Park, noticed that one of the earliest changes in the hind limb muscle cells of mouse models of ALS was elevated levels of a transcription factor, MyoD – a protein that either promotes or represses the expression of other genes.

Dr. Park hypothesized that the increased levels of MyoD might be a protective response by the muscle cells. So he designed an experiment to overexpress MyoD in the muscles of mouse models of ALS, thinking that this would slow down the disease.

The genes, encapsulated in a benign virus, were injected into the hind limb muscles, where the disease makes its first appearance. But instead of ameliorating their symptoms, it worsened them. The connections between motor neurons and muscles deteriorated more rapidly (known as denervation) and the motor neurons attached to the muscles were more likely to have degenerated.

When they looked at the muscles of the mice with increased levels of MyoD, they noticed that normally “slow-twitch” muscle fibres had been converted to the “fast-twitch” variety. Slow-twitch muscles rely on oxygen to contract more slowly but for longer periods; fast-twitch muscles rely on anaerobic respiration to contract quickly but get fatigued sooner.

With that insight, they injected mice with another transcription factor, MYOG, which is highly expressed in slow-twitch muscles, to see if they could convert the muscles from fast-twitch to slow-twitch. When they administered MYOG gene therapy to ALS mice, it slowed denervation of the target muscles and prevented the death of motor neurons attached to those muscles.

Neuron-muscle circuitry

“In ALS we focus on the fact that motor neurons die, and most of the effort in the field has been focused on saving these cells directly,” says Dr. Leavitt, a Principal Investigator at the Centre for Molecular Medicine and Therapeutics, and a neurologist at UBC Hospital who specializes in Huntington’s disease, ALS, and fronto-temporal dementia. “But motor neurons are just one part of the motor unit, which is like a circuit – a single unit made up of a motor neuron, the neuromuscular junctions and muscle fibres innervated by the motor neuron.

“So by treating cells other than the neuron itself, maybe you can actually protect the neuron. And the muscle is much easier to get to, therapeutically, than the central nervous system.”

Dr. Leavitt has a two-pronged plan to build off this finding. One prong will examine the effect of gene silencing agents that reduce levels of MyoD, because reducing expression of a gene is usually easier than promoting gene expression. He has already seen a significant benefit in the function and numbers of motor neurons, as well as survival, using this approach in ALS mice, and hopes to collaborate with Professor Pieter Cullis, in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, to use Dr. Cullis’ patented lipid nanoparticle delivery system to get the gene silencers through cell membranes.

Dr. Leavitt also plans to examine whether modulating muscle fibres from fast-twitch to slow-twitch through exercise can slow progression of the disease, and vice-versa. That would mean comparing ALS mice that do sprint training with counterparts that exercise at a slower pace for longer periods. His hunch is supported by studies showing that high performance athletes have a higher incidence of ALS than otherwise similar non-athletes.

“If you do exercise that increases your fast-twitch muscles, you might make yourself more vulnerable to ALS,” he says. “And if you do exercise that increases your slow-twitch muscle fibres, that might be protective – and that could be turned into exercise therapy for ALS patients.”

Falling dominoes

Neil Cashman’s theory is focused on “template-directed misfolding” – a process by which a protein assumes an abnormal molecular shape, and by that very action, induces like proteins to do the same. It’s akin to a line of falling dominoes, except the action extends in all directions, much the way a virus propagates throughout an organism.

Dr. Cashman has spent much of his career studying how this happens with prion protein, a normally harmless protein prone to template-directed misfolding. When enough prion proteins misfold, they clump together and become toxic, leading most famously to Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease, a fatal brain disorder in humans, or “mad cow disease” in cattle.

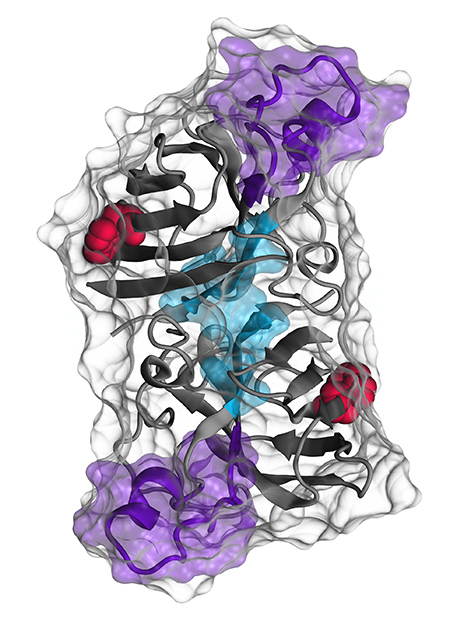

![A representation of the SOD1 protein being studied by Neil Cashman. The red areas are the amino acid tryptophan 32, which Dr. Cashman believes is the trigger for SOD1 misfolding. The aqua and purple regions are binding sites for antibodies developed by Dr. Cashman. Illustration courtesy of Cashman Lab.]()

A representation of the SOD1 protein being studied by Neil Cashman. The red areas are the amino acid tryptophan 32, which Dr. Cashman believes is the trigger for SOD1 misfolding. The aqua and purple regions are binding sites for antibodies developed by Dr. Cashman. Illustration courtesy of Cashman Lab.

Dr. Cashman, academic director of the Vancouver Coastal Health ALS Centre, thinks a similar process is at work in ALS – not with prion protein, but with a protein called SOD1. If true, it would illuminate a central mystery of ALS. Only 2 per cent of cases can be traced to a genetic mutation that produces a toxic version of SOD1. So why are motor neurons dying in people without that mutation?

When Dr. Cashman first found evidence of misfolded SOD1 in all types of ALS in 2007, he says it was almost heretical, and he couldn’t get it published in a high-impact journal. Within a few years, other scientists confirmed his findings, but “there is still scientific controversy as to whether SOD1 misfolding occurs in sporadic ALS.”

Even among those who accept the presence of misfolded SOD1 in ALS, Dr. Cashman stands out for flagging it as a final common pathway in all types of the disease, and for arguing that template-directed misfolding makes for an “infinite factory” of misfolded toxic SOD1.

“I’m convinced there is some prion-like process, in which a rogue, misfolded protein propagates by causing similar proteins to misfold in the same way,” he says. “Is it SOD1? I’m 95 per cent sure it is.”

A molecular dissection

The federal government, through the newly created Canada Brain Research Fund, was intrigued enough by Dr. Cashman’s hypothesis to award him and his collaborators a three-year, $1.5 million grant to undertake a “molecular dissection” of SOD1 misfolding.

Dr. Cashman, along with Professor of Zoology Jane Roskams, will seek further proof that SOD1 misfolding can spread from nerve cell to nerve cell, down the spinal cord to motor neurons.

With Jasna Kriz and Jean-Pierre Julien at Universite Laval in Quebec, he will measure the effect of two antibodies (one developed by Dr. Cashman and the other by Dr. Julien) that bind to misfolded SOD1, neutralizing it and thus interrupting the domino-like misfolding process. The antibodies will be given to some ALS mice before symptoms appear, and to other ALS mice after the disease has already started to take its toll.

Two other experiments are focused on proving whether an amino acid component of SOD1, tryptophan 32, is the trigger for SOD1 misfolding. Dr. Julien will breed mice without tryptophan 32 to see whether that deficiency arrests the misfolding process and enables ALS mice to resist the symptoms. Dr. Cashman will manipulate tryptophan 32 in various ways to determine precisely what makes it a trigger.

“If you lack this amino acid, you don’t have the propagation,” he says. “It could be just a handful of atoms enabling this process, and if that’s the case, it would be a tempting target for a therapy.”

When Laura Bulk, MOT’14, is on the job as an occupational therapist, she helps people who were injured in motor vehicle accidents continue doing the activities that bring meaning to their lives.

When Laura Bulk, MOT’14, is on the job as an occupational therapist, she helps people who were injured in motor vehicle accidents continue doing the activities that bring meaning to their lives.